CHINA

24 July 2021

The Chinese Communist Party celebrates – but for how long?

Lavish centenary celebrations marked 100 years of the CCP, but they mask several internal tensions and insecurities, writes John West.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has just celebrated the 100th anniversary of its founding. It is now the biggest and most powerful political party in the world. It is dominated by its General Secretary Xi Jinping, who has also been Chairman of the Central Military Commission and President of the People’s Republic of China since 2012/13. President Xi is China’s most powerful leader since Chairman Mao Zedong, and arguably the world’s most powerful political figure today.

This was not supposed to happen. Can it last?

The reality has proved to be quite the opposite. Many of China’s middle and upper classes are not great supporters of democracy, as they have been substantial beneficiaries of China’s rapid economic development, and rising inequality. And many are indeed members of the 90+ million strong CCP. Rather, they are supporters of the status quo, and often fear the possible impact of allowing the whole population to have a say in their nation’s politics. They often look upon poorer, rural populations as uneducated country bumpkins, who represent a potential threat to their privileged position.

Another reaction of those in China’s middle and upper classes who may want democracy and freedom, has been to opt out by migrating to countries like the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Recent years have seen large flows of Chinese migration to these countries, together with massive investments in real estate and illicit financial outflows.

And then there were many analysts who thought that the advent of the internet and social media could fuel democratisation, as they provide citizens with unprecedented access to information and with effective tools for political mobilization. But the internet and social media have proved to be two-edged swords in China. The government has responded by imposing censorship controls on the internet (like China’s great firewall), by disseminating propaganda through the internet, and by using the internet for the surveillance of its citizens, as seen in China’s infamous social credit system.

There are also many reasons why Western democracy is seen in a bad light in China. The British referendum to leave the EU (Brexit), the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the US, and the mismanagement of COVID-19 in the US, UK and much of Western Europe are seen as failures of democracy.

Until recently, the CCP has also received unwitting support from many Western governments and businesses that have tread very softly on China’s one-party rule and its human rights abuses in return for the attraction of China’s big market and the desire to cooperate with China on issues like climate change.

Fundamentally, Western discussions and debates on the possible opening up and democratisation of China are often based on a complete misunderstanding of the CCP’s worldview. The CCP sees itself as the saviour of China and Chinese civilisation from both the century of humiliation inflicted by Western countries and its civil war rival – the Chinese Nationalist Party. Continued CCP rule is thus essential for China’s national security and prosperity, notably protecting China from the US, the greatest external challenge to its national security, sovereignty and internal stability.

Mr Deng set the parameters for Chinese foreign policy with his dictum, “Hide your capacities, bide your time”. He also played a crucial role in shaping the CCP’s governance. Mr Deng once bravely stated that Chairman Mao was “70% right and 30% wrong”. And following the excesses of his authoritarianism, Mr Deng encouraged collective leadership, whereby CCP leaders should govern by consensus. Under his leadership, it was decided that China’s president could only serve two consecutive terms.

President Xi and his colleagues also interpreted the 2008/9 Global Financial Crisis as a sign of American decline, and a strategic opportunity for China – no more “hide and bide”. The US and China are now declared rivals, and although US President Biden has already met with Vladimir Putin, he has not yet made any effort to meet with President Xi. Indeed, he is being treated like a pariah by the West, something which must be an embarrassment to the very proud and nationalist Chinese people.

Motivated by internal insecurity and a naive sense of international strength, President Xi drove the country forward with his China dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people. This combined increased repression and human rights abuses at home, a shift back towards a more state-led economy, strident nationalism, and a resurrection of the historical importance of Chairman Mao, along with greater assertiveness internationally.

It was this combination that characterised President Xi’s response to COVID-19 – initial coverup and lack of transparency, successful containment through draconian lockdowns, “wolf-warrior diplomacy”, and brazen triumphalism which has received a very frosty reception by the West, most notably at the recent G7 and NATO summits.

How are we to interpret President Xi’s position and that of China today, as the CCP turns 100? President Xi and the CCP look on top of the world, as they dominate China and look more solid than the fragile West. And yet, the reality could be quite different.

China’s economy looks wobbly – with its ageing population, enormous public debt, an increased emphasis on the role of inefficient state-owned enterprises, and an education system where patriotic propaganda plays a growing part. The tech war with the US is depriving Chinese tech companies of key parts and components, and President Xi’s calls for technological self-reliance and independence seem like a pipe dream, for now. China’s international relations have rarely been worse in the post-Mao period – hardly an ideal situation for an aspiring world leader. And the next generation of Chinese leaders, who will likely be deprived of their deserved positions by a Xi Jinping who hangs on as leader, cannot be happy.

If there is one thing history teaches us, it is that authoritarian regimes are usually brittle—even if they seem not—and that political change can come suddenly. A possible scenario for 2022 might be a reshuffling of the CCP leadership, and a less confrontational posture towards the West.

This was not supposed to happen. Can it last?

China’s failure to democratise

It wasn’t so long ago that US political leaders like former President Bill Clinton were predicting that the opening of the Chinese economy would naturally lead to an opening of its society and political system. This idea was built on the work of American political scientists who predicted that economic development together with growing middle classes, education and urbanisation would naturally foster democratisation.The reality has proved to be quite the opposite. Many of China’s middle and upper classes are not great supporters of democracy, as they have been substantial beneficiaries of China’s rapid economic development, and rising inequality. And many are indeed members of the 90+ million strong CCP. Rather, they are supporters of the status quo, and often fear the possible impact of allowing the whole population to have a say in their nation’s politics. They often look upon poorer, rural populations as uneducated country bumpkins, who represent a potential threat to their privileged position.

Another reaction of those in China’s middle and upper classes who may want democracy and freedom, has been to opt out by migrating to countries like the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Recent years have seen large flows of Chinese migration to these countries, together with massive investments in real estate and illicit financial outflows.

And then there were many analysts who thought that the advent of the internet and social media could fuel democratisation, as they provide citizens with unprecedented access to information and with effective tools for political mobilization. But the internet and social media have proved to be two-edged swords in China. The government has responded by imposing censorship controls on the internet (like China’s great firewall), by disseminating propaganda through the internet, and by using the internet for the surveillance of its citizens, as seen in China’s infamous social credit system.

There are also many reasons why Western democracy is seen in a bad light in China. The British referendum to leave the EU (Brexit), the election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the US, and the mismanagement of COVID-19 in the US, UK and much of Western Europe are seen as failures of democracy.

Until recently, the CCP has also received unwitting support from many Western governments and businesses that have tread very softly on China’s one-party rule and its human rights abuses in return for the attraction of China’s big market and the desire to cooperate with China on issues like climate change.

Fundamentally, Western discussions and debates on the possible opening up and democratisation of China are often based on a complete misunderstanding of the CCP’s worldview. The CCP sees itself as the saviour of China and Chinese civilisation from both the century of humiliation inflicted by Western countries and its civil war rival – the Chinese Nationalist Party. Continued CCP rule is thus essential for China’s national security and prosperity, notably protecting China from the US, the greatest external challenge to its national security, sovereignty and internal stability.

The evolution of the CCP

The CCP has, of course, evolved over the past century – from the handful of people who created it in 1921 and then the civil war period, through to the unstable and disastrous years under Chairman Mao and the success of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and opening up. Mr Deng’s economic reforms from 1978 launched an extraordinary period of economic growth and poverty reduction, such that in four decades this once miserably poor country became a global power and political rival of the US.Mr Deng set the parameters for Chinese foreign policy with his dictum, “Hide your capacities, bide your time”. He also played a crucial role in shaping the CCP’s governance. Mr Deng once bravely stated that Chairman Mao was “70% right and 30% wrong”. And following the excesses of his authoritarianism, Mr Deng encouraged collective leadership, whereby CCP leaders should govern by consensus. Under his leadership, it was decided that China’s president could only serve two consecutive terms.

President Xi revolutionises Mr Deng’s paradigm

The rise of President Xi to China’s leadership has led to a revolution in Chinese politics, as he has overthrown much of Mr Deng’s legacy. To his credit, he saw the CCP in a perilous situation with rampant corruption, an enormous debt burden, and environmental problems that were undermining public support. He also had to dispose of attempted coup leader, Bo Xilai, and other rivals as he consolidated power. He has centralised all government functions around himself, and secured the abolition of presidential term limits.President Xi and his colleagues also interpreted the 2008/9 Global Financial Crisis as a sign of American decline, and a strategic opportunity for China – no more “hide and bide”. The US and China are now declared rivals, and although US President Biden has already met with Vladimir Putin, he has not yet made any effort to meet with President Xi. Indeed, he is being treated like a pariah by the West, something which must be an embarrassment to the very proud and nationalist Chinese people.

Motivated by internal insecurity and a naive sense of international strength, President Xi drove the country forward with his China dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people. This combined increased repression and human rights abuses at home, a shift back towards a more state-led economy, strident nationalism, and a resurrection of the historical importance of Chairman Mao, along with greater assertiveness internationally.

It was this combination that characterised President Xi’s response to COVID-19 – initial coverup and lack of transparency, successful containment through draconian lockdowns, “wolf-warrior diplomacy”, and brazen triumphalism which has received a very frosty reception by the West, most notably at the recent G7 and NATO summits.

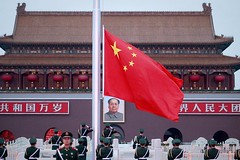

CCP’s extravagant celebration of its 100th birthday

On 1 July, the CCP held an extravagant celebration of its 100th anniversary with a typically long speech by President Xi, peppered with bravado and warnings to the rest of the world. The message was clear, “don’t mess with China”.How are we to interpret President Xi’s position and that of China today, as the CCP turns 100? President Xi and the CCP look on top of the world, as they dominate China and look more solid than the fragile West. And yet, the reality could be quite different.

China’s economy looks wobbly – with its ageing population, enormous public debt, an increased emphasis on the role of inefficient state-owned enterprises, and an education system where patriotic propaganda plays a growing part. The tech war with the US is depriving Chinese tech companies of key parts and components, and President Xi’s calls for technological self-reliance and independence seem like a pipe dream, for now. China’s international relations have rarely been worse in the post-Mao period – hardly an ideal situation for an aspiring world leader. And the next generation of Chinese leaders, who will likely be deprived of their deserved positions by a Xi Jinping who hangs on as leader, cannot be happy.

If there is one thing history teaches us, it is that authoritarian regimes are usually brittle—even if they seem not—and that political change can come suddenly. A possible scenario for 2022 might be a reshuffling of the CCP leadership, and a less confrontational posture towards the West.