ASIA

08 June 2015

Asia's global value chains -- Part 2

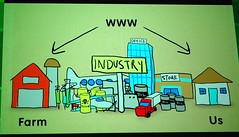

Global value chains entail many risks and challenges, which are addressed in this note.GVC risks and challenges

Participation in GVCs can expose economies to a wide range of risks, challenges and shocks.The 2008 Lehman shock and the global financial crisis marked the beginning of a new phase in Asia’s GVCs. The initial recession the US and Europe greatly reduced demand for Asia’s GVC products. During the 2008-2009 recession, international trade fell five times more than global GDP, the “great trade collapse”. And ever since there has been protracted sluggish growth in advanced markets.

These events highlighted the unbalanced, mercantilistic, nature of Asia’s GVC-based development strategy. Most Asian countries had directly or indirectly assisted the development of GVCs through incentives, subsidies and concessions, to the detriment of the domestic economy. They had also banked on continued strong growth in advanced economy markets. While Asia’s GVCs will remain important, these economies are now in the midst of “rebalancing” their economies, by seeking to strengthen the domestic economy, and also target Asian markets.

This rebalancing agenda is proving challenging, as East Asian had staked so much on GVC-based development, and there are naturally vested interests who are resisting change. China now has an excess capacity problem in industries like tyres, steel and solar panels. In an endeavour to stay afloat Chinese producers are flooding global markets with these products, contributing to global deflation. And as Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak and Huanhuan Zheng have argued, China is now undertaking “outwards mercantilism”, as its foreign direct investment is increasingly bundled together with the export of Chinese manufactured products and labor services, as one way to use its excess capacity.

But other factors have been coming into play. Chinese wages have been increasing strongly, as its pool of “surplus labor” is becoming exhausted, thereby reducing its attractiveness as low-cost destination. Low-cost GVC production has thus been migrating elsewhere, like Vietnam, Cambodia and Bangladesh. China will no longer be able to base its competitiveness on being a low-cost country. Future competitiveness must come from innovation, creativity and higher productivity.

Another related trend is that of “reshoring” or “insourcing” production back to the US, Europe and Japan. This contraction of GVCs is in part due to rising costs of production in Asia. Other factors behind reshoring are falling US domestic energy prices, and improved US productivity following post-crisis restructuring. Rapid technological change is also playing an important role through robotics, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, and the internet of things, as they erode Asia’s low-cost attractiveness. Indeed, John Lee of the Hudson Institute has argued that robotics and 3-D printing might even kill the Asian Century, and that Asia’s newly emerging economies will needed a changed model from the “export manufacturing” that drove development in Japan, Korea and Taiwan.

Some observers also argue that offshoring to Asia had become a fad, with many companies being seduced by low labor costs and not taking account all of the hidden costs. For example, outsourcing also puts you at a time-disadvantage in getting products to market. Improved technology now allows very rapid cycle production close to the US market inside the US. Another lesson is that the co-location of manufacturing and R&D can exploit the obvious synergies

Insourcing makes it easier to protect intellectual property, a big issue especially in China. And since President Xi Jinping came to office, many foreign companies have experienced increasing costs and frictions of doing business in China, as they are harassed over issues like monopoly pricing and corruption.

Maintaining adequate quality control is also critical. China has been littered with many scandals regarding the quality of food and other products in recent years -- to such a point that Chinese citizens often travel abroad, especially to Hong Kong, to buy safer internationally branded food products. In recent years, Japan has also been a victim of several scandals regarding poisoned food emanating from China. Just one Chinese company with bad practices can taint the whole Chinese industry reputation. This highlights the necessity for the Chinese government to have and above all to enforce high product quality standards in order to promote “brand China”. But the tales from Paul Midler’s “Poorly Made in China” highlight how difficult an issue product quality is China.

Obviously, there is no likelihood of everything being reshored back to America. And the strongly growing Asian middle class is another reason to invest in the region. But in addition to some American firms coming back home, many Chinese manufacturing companies are now investing in the growing US economy. In short, a country's position in the supply chain can also never be taken for granted.

Asia’s GVCs are also highly exposed to natural disasters like tsunamis, earthquakes and floods, since Asia is the region of the world most afflicted by such disasters, which have increased considerably in frequency in recent decades. In recent times, Japan’s 2011 triple disaster disrupted the supply of components to automotive and electronics GVCs. Indeed, some GVCs temporarily broke down, reflecting their very high dependence on Japan’s high-tech parts and components.

Flooding in Thailand, also in 2011, disrupted Japanese automobile and electronics producers. The flooding inundated areas accounting for 45% of the world manufacturing capacity of computer hard disk drives. One factor inhibiting greater extension of GVCs to the Philippines is this country’s extreme vulnerability to natural disasters. Clearly companies must better manage these natural disaster risks of GVCs, with reshoring being one option for diversifying component sourcing. And disaster-prone countries like the Philippines must greatly improve their disaster risk management systems to become more attractive for GVCs.

Political and social instability can have adverse effects. Political tensions in recent years between China and Japan led to physical attacks on Japanese products and production facilities. They have affected demand for Japanese products by Chinese consumers. As a consequence, Japanese business has been turning away from China towards the Southeast Asian economies (ASEAN) and India. In 2013, Japanese investment in ASEAN grew 2.2 times over the previous year to $23.6 billion, marking historical high, while investment in China fell 32.5% to $9.1 billion. This switching of investment away from China continued into the early months of 2014.

The economic costs of China’s foreign policy posture towards Japan have become evident to the Chinese leadership, and has been one factor behind the calming down of tensions. With an increasingly wobbly economy at home, China cannot afford to scare away good FDI.

The local environment in China and other Asian countries has also suffered greatly, as advanced countries have offshored their dirty industries, taking advantage of soft environmental regulations, especially in special economic zones, and weak implementation of such regulations where they exist. Such weak implementation is one of the many manifestations of corruption in Asia. Now that China is suffering so much from a polluted environment, it is regrettable that one of its solutions is to offshore some of its dirty industries to poorer countries.

Moving up the GVC

Most emerging and developing Asian economies only make a minor contribution to the value of Asia’s GVC products, as the examples of the iPhone and the jacket at the beginning of this chapter highlight. Indeed, they are more passive ‘recipients’ of GVCs, rather than creators. The challenge is to climb the GVC and to contribute more value through functions such as high tech componentry, product design, branding etc, and to ultimately become a creator of GVCs. If a country does not make the effort to contribute more value, it can get caught forever at a low value added point on the GVC, and stuck in a middle income trap.How does a country move up the GVC?

The very act of participating in GVCs facilitates knowledge and technology transfers. Local people who work in multinational enterprises gain valuable experience and exposure to global best practices. Local companies who have supply contracts with multinationals also learn to comply with the global product standards. In other words, GVCs provide an opportunity for learning by doing, as knowledge can flow along GVCs and lay the foundation for them to make a high value added contribution to GVCs.

But experience shows that passive upgrading may not take you a long way up the GVC. Many GVCs are located in special economic zones, which can be isolated from the rest of the economy. MNEs may only undertake simple processing, without the participation of local enterprises. In 2009, nearly half of China’s exports originated from special economic zones, while one-third of its imports were bound for such zones. And around two-thirds of China’s “processing trade” was undertaken by multinational enterprises.

Public and private investments in R&D, along with creating an effective innovation system, are necessary to raise a country’s technological capacity. Stronger investments in human capital, and infrastructure are also key, as is an ecosystem that fosters entrepreneurship. Asia’s best success stories of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore have moved up the GVC through doing exactly just that.

The Japanese and Korean governments also provided great protection against imports and foreign investments to give their companies some breathing space for industrial upgrading. And these are the only Asian countries to establish strongly branded enterprises and products, that compete head-to-head with the Western companies.

But such developmental state policies are anathema to today’s world of GVCs where openness to imports and foreign investment are key to hooking on to GVCs. It is now much more effective to try to attract foreign investment in R&D facilities. For example, GE innovates through “Global Research Centres” located in Bangalore, Munich, Shanghai, Niskayuna (New York) and Rio de Janeiro

Many eyes are today watching China to see how far it will be able to climb the GVC, which it now must in light of increasing wage costs at home. It is perhaps the most pro-active Asian country when it comes to trying to push its way up the GVCs. China is seeking to become a major player in global innovation with large R&D investments in space programs, aerospace, renewable energy, computer science and life science. Purchases of Western and Japanese companies, such as the cases of Lenovo’s purchase of IBM’s personal computer business and Haier’s acquisition of part of Japan’s Sanyo, were also motivated by the desire to gain access to technology.

Reflecting the state-dominated nature of the Chinese economy, the government is very active in seeking to promote upgrading through industrial policies in areas like automobiles, steel, telecommunications, and aircraft. The Chinese government would like to see “made in China” replaced by “created in China”. All too often this means protection and subsidies, rather than exposing the economy more to the healthy winds of free competition.

The Chinese government is well aware that multinational companies do not share their intellectual property very easily, especially given China’s weak intellectual property protection. Thus, it will often attach strong technology sharing and transfer conditions to investments, including through obliging multinationals to enter into joint ventures and establish R&D centres. Chinese companies are also very aggressive in industrial espionage for intellectual property theft, reportedly often with government/military participation and support.

The Chinese government clearly believes that the attractiveness of the large Chinese market gives it a license to play hardball with multinational companies. While some Chinese companies no doubt benefit from this, it also feeds a climate of deep strategic distrust which undermines the foundations for open innovation partnerships. And as the Chinese economy slows while India is taking off again, it is clear that China is not the only game in town.

What is the evidence on China’s upgrading? China has made progress in moving up the value chain across a vast range of product areas. The domestic value added share of China’s exports has been increasing, although this could also reflect a rise in the share of China’s lower grade exports from companies like Haier and Xiaomi to developing country markets. Aside from the great success of Alibaba, China does not yet have any big brand names to rival the big brands of Japan and Korea. Many question whether big new ideas are possible in a system with such widespread and growing censorship, and lack of intellectual and cultural freedom of expression. And the aping of Apple’s Steve Jobs by Xiaomi’s Lei Jun suggests that China is still very much at the copycat stage of development.

Trade and investment liberalisation for GVCs

The opening of Asian economies to more trade and investment has clearly been a factor fostering the development of GVCs. The possibility of further market opening at the global level, through trade negotiations under the World Trade Organisation, has been bogged down for over a decade, with these negotiations being now basically abandoned.At the same time, there has been a flurry of activity at the regional level in Asia. Building on the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement of the Southeast Asian countries, there is now a “noodle bowl” of free trade agreements criss-crossing Asia, between ASEAN and China, Japan, Korea, Australia, India and New Zealand. Negotiations are now underway to bring these all together in a “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership” (RCEP).

Many are billing this as an initiative of Chinese economic leadership in the region, especially given that the US is not involved. But most astute observers note that these free trade agreements are shallow, focussing on tariff barriers rather than addressing non-tariff barriers and facilitating trade in a way that is helpful for GVCs. Moreover, the RCEP is unlikely to result in further liberalisation beyond the bilateral agreements, despite the announced intentions to break new ground. The basic point is that, outside of the cases of Hong Kong and Singapore, most Asians do not believe in free trade. Indeed, China, India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam have been among the worst offenders in the burgeoning trade protectionism since the 2008 Lehman shock, according to the Global Trade Alert.

Another factor minimising the impact of RCEP is that much of Asia’s GVC trade is conducted out of special economic zones, or through special arrangements, which give foreign investors access to duty free imports. Such access is granted as an incentive or concession to foreign investors, especially since the entry of imports is fundamental to the assembly or other processing of products for export.

So in short, further reductions of import tariffs through the RCEP are unlikely to have any effect on market openness for GVCs. The real barriers facing GVCs are non-tariff barriers, notably red tape, regulations, and corruption. These will not be solved by RCEP.

There is another set of trade talks underway across the Pacific known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, and which are led by the US and do not include China. The TPP is currently being negotiated by the following twelve countries -- Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, USA, Vietnam.

Geopolitical strategists like to speculate that the TPP is an American conspiracy against China. The reality is that China was invited to join the TPP talks, and declined. And despite some subsequent grumbling, China is perfectly relaxed about TPP, and may even apply to join it one day.

The TPP is billed as a landmark, 21st-century trade agreement, setting a new standard for global trade and incorporating next-generation issues that will boost the competitiveness of TPP countries in the global economy. The negotiations cover all aspects of commercial relations among the TPP countries, things like competition policy, cross-border services, customs, e-commerce, environment, financial services, government procurement, intellectual property, investment -- and a whole lot more. China is not ready to commit itself to vast array of obligations that the TPP entails, in light of its vast array of state-owned enterprises and banks, many of which hold monopoly positions in the local market.

Will TPP make a difference? Some perhaps. But some of the participating countries already have free trade agreements between themselves, and some are also very small. The TPP “is in large part a Japan story and a Vietnam story,” according to Peter A. Petri, a professor of international finance at Brandeis University. These two countries do not have FTAs with most of the other participants.

But as other observers have remarked, the TPP addresses the 21st century business realities by dealing the full range of business issues relevant to GVCs. In particular, weak protection of intellectual property and investor rights hurts GVCs because offshoring increases the international exposure of a firm’s knowledge and capital. The hope is that the TPP will be establishing a benchmark for future GVC-oriented trade agreements, with great potential benefits in the future should China and India ultimately join up.

Services are the Achilles heel of Asia’s big developing countries, according to a recent OECD study. China, India and Indonesia suffer from very high restrictions on their trade in services. These restrictions are often two to three times higher than in the advanced OECD countries. They are an important reason why service sector productivity in these countries is lower than in their manufacturing sectors, and also very much lower than in service sectors in OECD countries. World class service sectors cannot be developed if isolated from best international practice and world class inputs.

Moreover, inefficient service sectors are also a great barrier to these countries’ participation in GVCs. There can never be effective GVCs without well-functioning transport, logistics, finance, communications and other business and professional services to move goods and coordinate production across the economy. Unfortunately, none of the trade talks underway will result in the removal of these services trade restrictions.

Business process outsourcing is no panacea

The advances and diffusion of information technology have opened up new opportunities for the creation of GVCs for many business services, known as business process outsourcing (BPO). Services which are most offshorable, are those which are routine, and which are electronically deliverable and don't require face-to-face contact with customers, as does a haircut.The BPO sector began with call centers, and then extended to tele-marketing, accounting, legal, human resources, software development, medical transcription, etc. In other words, a services GVC has blossomed to join the much celebrated manufacturing GVCs. Industries typically served by the BPO sector include travel, banking and insurance, accounting and legal, telecommunications, and information technology.

India and the Philippines, more than any other Asian countries, have been able to seize the opportunities of the BPO sector thanks to several factors -- good English language skills, low wage costs, and a large youthful workforce to choose from. For some time, India was the BPO front runner. But according to market reports, the Philippines has leapt ahead to become Asia's call center leader, with India losing a great chunk of its business to the Philippines. Citibank, Safeway, Chevron and Aetna are just a few of the international corporations to have BPO operations in the Philippines.

Filipinos, who mainly service the American market, reportedly have a better mastery of American English, and a greater cultural affinity with America than do Indians. The Philippines also produce more high quality graduates, especially in the accounting and legal fields.

The Philippine government has also provided greater support to the BPO sector than the Indian government. Most BPO offices are designated as special economic zones, with benefits like tax holidays, duty-free import of capital equipment, simplified import and export procedures, and freedom to employ foreign nationals. The passage of the Data Privacy Act has also put in place international data privacy standards, which are beneficial especially for the multitude of sensitive information like banking and insurance details handled by the BPO sector.

Call centers and associated BPO services now employ more than one million Filipinos, an increase of ten times over the past decade. The BPO sector, which has become the country's fastest growing industry, will bring in over $20 billion in revenues in 2015, not far behind the $26 billion the country will likely earn in migrants' remittances. However, the majority of these revenues come from voice call centers, as opposed to more technical IT outsourcing where India still retains an edge.

Overall, BPO sector now makes up 6% of the Philippines' GDP. But it has tended to be an economic enclave, with very little interaction with the rest of the economy, according to an Asian Development Bank study. Overall, it is neither a large buyer nor provider of inputs to other sectors of the economy. Its main impacts have been through the retail and real estate sectors.

But one point that should not be underestimated is that the Philippines’ dynamic BPO sector has helped improve the international perception of the country. Despite its enduring challenges, the Philippines is no longer written off by investors as the “sick man” of Asia.

Could BPO activities become a key driver of economic development in India and the Philippines, as manufacturing has been in countries like Japan, Korea and China?

Most regrettably, the BPO sector seems unlikely to become a key driver of economic development, despite the sector's many benefits. It is no development panacea. The BPO sector only offers employment to the relatively well educated, and not to the vast swathe of lower-skilled people who need jobs. Only 2% of the Philippine work force is employed in the BPO sector.

Both India and the Philippines need a manufacturing renaissance to offer employment to the lower-skilled. In both cases, this would require a much more investor-friendly environment, and a massive improvement in their physical infrastructure. It is thus not surprising that the Philippines' BPO boom has had little or no effect on the countries large outward migration.

The BPO sector is also problematic in other ways. Overqualified workers undertake rather low-skilled jobs, since even call centers usually require at least a two-year college education and excellent oral and written English. Professionals such as doctors are attracted by the higher salaries, and can waste their hard-earned education.

Many call center jobs entail working through the night, and doing monotonous tasks, and are not compatible with healthy living or a family life. This means that high staff turnover and job hopping are endemic. Moreover, such jobs usually do not offer the possibility of a career.

The opportunity does exist to exploit more benefits, by moving up the BPO value chain, and doing higher value added activities. And the Philippines has been doing just that in the areas of web design, software development and animation.

But as with the case of manufacturing GVCs, climbing further up the value chain will require much greater investments in human capital, and infrastructure to attract greater foreign investment in higher value added activities, as well as fostering a more entrepreneurial culture at home.

Remaining competitive in the BPO sector will also be a constant challenge. BPO activities can also have a footloose character, as evidenced by the rapid rise in the Filipino BPO sector at the expense of India. Other countries like China and Vietnam are now moving into the BPO market, and competition will no doubt remain ruthless. It is thus now the time to give small Philippine companies the chance to participate more actively in the BPO sector, such as by offering them the same incentives that are currently being offered to foreign-owned companies.

REFERENCES:

- OECD. INTERCONNECTED ECONOMIES: BENEFITING FROM GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS- Chinese Outwards Mercantilism - the Art and Practice of Bundling Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak, Huanhuan Zheng. NBER Working Paper No. 21089. Issued in April 2015

- Will Robots Kill the Asian Century? John Lee. The National Interest, April 23, 2015.

- Poorly Made in China: An Insider's Account of the Tactics Behind China's Production Game. Paul Midler.

- The Global Trade Disorder – The 16th GTA Report