ASIA

01 June 2014

OECD -- a Lilliputians' club

The OECD was once called the "hub of globalization" by its secretary-general, Angel Gurria. Not through any fault of its own, it is now looking more and more like the "hub of Lilliputians".

The OECD was once called the "hub of globalization" by its secretary-general, Angel Gurria. Not through any fault of its own, it is now looking more and more like the "hub of Lilliputians".

The OECD has a long and distinguished history. In the 1950s, as the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation, it managed the very successful Marshall Plan, which made an important contribution to the reconstruction of Europe after World War 2. For some three decades after its official birth in 1961, it was the place where economic leaders from the Western world huddled together to design and coordinate their economic policies. It was a sort of "economic NATO".

The end of the Cold War in 1989 led some like Francis Fukuyama to speculate that we had arrived at the "end of history". The very values that OECD stood for -- pluralist democracy, respect for human rights and market economy -- seemed to have won the day.

As the temple of Western values, the OECD opened its doors to cooperation with non-member economies, to share the wisdom, expertise and experience of the economic and political model that had won the prize of history. It seemed just a matter of time before emerging and transition economies from the world over would be knocking at its doors for membership.

Sure enough, Mexico joined in 1994, such that the three members of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) were by then OECD members. Korea, a genuine miracle of economic development and democracy, then joined in 1996. Both countries were struck down by financial crises not long after their membership -- prefiguring the doom that was awaiting the leading OECD economies one decade later in the global financial crisis.

OECD membership by the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia would follow. This proved to be the "Lilliputian prefiguration". Apart from Poland, they are all rather small economies, a trend that would be followed in the subsequent membership of Chile, Estonia, and Slovenia. Colombia and Latvia are now in the midst of the OECD's arduous membership process. This requires satisfying expert committees of their country's ability and willingness to broadly align their policies with the mind-boggling tomes of accumulated OECD wisdom. Costa Rica and Lithuania are also in the membership queue, but a bit further back.

The OECD undertakes excellent work with a vast range of non-member economies, notably the BRIICS of Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China and South Africa. A new program is being launched with South-East Asia. (Unfortunately, Thailand, which was once a plausible candidate for OECD membership, has now been struck down by a military coup.)

OECD's work with non-members has only grown in importance since the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Its analysis and recommendations have become ever more relevant in areas of financial regulation, taxation, social policy, education, and macro-economic policy.

But the interest of the BRIIC countries in OECD membership, always lukewarm, is waning further. Russia's 1996 application for membership has been bogged down ever since, in large part due to a lack of seriousness on the Russian side. Now that Russia has effectively declared war on the West, its possible OECD membership is certainly off the table.

China, as the archetypal free rider on the international system, is very happy to participate in OECD activities of interest to it. This is consistent with its general policy of swallowing as much information and technology as it can from the rest of the world (could it also be undertaking cyber-espionage of the OECD's massive databases?). But China would never join a club that it didn't have a hand in designing. And democracy and human rights are most certainly not on the Communist Party's agenda.

For its part, India has always been fiercely independent, with no desire of being a close ally of anyone -- most certainly not a club of former colonial powers.

What is the OECD problem?

Membership of the OECD means accepting the rules established by the pre-existing membership, and not being allowed to shape those rules. You must become a "rule-taker", rather than a "rule-maker" -- something which is not attractive to any emerging global power.

Perhaps the most onerous requirement of OECD membership is policy transparency, something which fragile democracies and authoritarian regimes are uncomfortable with. OECD committee meetings may be a little boring, but the deal is that all member countries open up with each other, and share detailed information on what's happening in their economy.

Most fundamentally, despite globalization, the OECD still remains a club of the West, substantially influenced by the US. And while joining a Western club may be attractive for countries like Costa Rica and Lithuania, it is not necessarily the case for the BRIICS.

The reality is that 25 years after the end of the Cold War, there is still a curtain between the West and the "Rest", even though it is no longer an iron curtain.

True, economic globalization is forging vast links between the West and "the Rest". Policy dialogue between governments is widespread. International tourism, students, and the Internet mean that there are also great webs of person-to-person contact.

But even in the best of cases, "the Rest" do not practice very well the Western values of pluralist democracy, respect for human rights and pluralist democracy. And resorting to conflict and harassment as means of international dispute resolution is now avoided wherever possible by Western countries, in contrast to countries like China and Russia. Perceived injustices from past history still motivate mindsets in these countries.

As to India, minor incidents, like the arrest of a junior diplomat for breaking the US law, can flair up into virtual nuclear warfare, highlighting the psychological scares of colonial history.

Assertive behavior by Australia in relation to boatloads of refugees passing through Indonesia to the vast Australian coastline has done immense damage to the always delicate Australia-Indonesia relationship. And the demise of Indonesia's Suharto regime at the hands of the Asian financial crisis, and arguably at the hands of the US-dominated International Monetary Fund, is still very much in living memory.

In short, despite the end of the Cold War, we are still a very long way from the end of history. Deep fundamental differences remain between the West and the "Rest".

And the West has contributed to this. America's credibility suffered greatly from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The global financial crisis represented a further shock for the West's brand of capitalism. The euro crisis has cast grave doubts over the benefits of close economic integration. Japan's never-ending crisis, which some interpret as being provoked by US pressure to revalue the yen, further undermine trust in American intentions -- could the US be trying to weaken China, as it succeeded in doing to Japan? And Snowdon's revelations of the National Security Agency's activities only deepened further the widespread distrust of the US.

All of this means that the OECD's one-time quest of becoming the "hub of globalization" will remain a pious hope. The Organisation is and will remain a vestige of Western dominance, despite its excellent work. In today's multi-polar world, the OECD just represents one pole!

In today's world, OECD membership is only attractive for small countries with great aspirations -- the Lilliputians of this world.

Executive Director

Asian Century Institute

The OECD has a long and distinguished history. In the 1950s, as the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation, it managed the very successful Marshall Plan, which made an important contribution to the reconstruction of Europe after World War 2. For some three decades after its official birth in 1961, it was the place where economic leaders from the Western world huddled together to design and coordinate their economic policies. It was a sort of "economic NATO".

The end of the Cold War in 1989 led some like Francis Fukuyama to speculate that we had arrived at the "end of history". The very values that OECD stood for -- pluralist democracy, respect for human rights and market economy -- seemed to have won the day.

As the temple of Western values, the OECD opened its doors to cooperation with non-member economies, to share the wisdom, expertise and experience of the economic and political model that had won the prize of history. It seemed just a matter of time before emerging and transition economies from the world over would be knocking at its doors for membership.

Sure enough, Mexico joined in 1994, such that the three members of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) were by then OECD members. Korea, a genuine miracle of economic development and democracy, then joined in 1996. Both countries were struck down by financial crises not long after their membership -- prefiguring the doom that was awaiting the leading OECD economies one decade later in the global financial crisis.

OECD membership by the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia would follow. This proved to be the "Lilliputian prefiguration". Apart from Poland, they are all rather small economies, a trend that would be followed in the subsequent membership of Chile, Estonia, and Slovenia. Colombia and Latvia are now in the midst of the OECD's arduous membership process. This requires satisfying expert committees of their country's ability and willingness to broadly align their policies with the mind-boggling tomes of accumulated OECD wisdom. Costa Rica and Lithuania are also in the membership queue, but a bit further back.

The OECD undertakes excellent work with a vast range of non-member economies, notably the BRIICS of Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China and South Africa. A new program is being launched with South-East Asia. (Unfortunately, Thailand, which was once a plausible candidate for OECD membership, has now been struck down by a military coup.)

OECD's work with non-members has only grown in importance since the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Its analysis and recommendations have become ever more relevant in areas of financial regulation, taxation, social policy, education, and macro-economic policy.

But the interest of the BRIIC countries in OECD membership, always lukewarm, is waning further. Russia's 1996 application for membership has been bogged down ever since, in large part due to a lack of seriousness on the Russian side. Now that Russia has effectively declared war on the West, its possible OECD membership is certainly off the table.

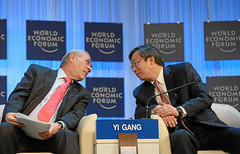

China, as the archetypal free rider on the international system, is very happy to participate in OECD activities of interest to it. This is consistent with its general policy of swallowing as much information and technology as it can from the rest of the world (could it also be undertaking cyber-espionage of the OECD's massive databases?). But China would never join a club that it didn't have a hand in designing. And democracy and human rights are most certainly not on the Communist Party's agenda.

For its part, India has always been fiercely independent, with no desire of being a close ally of anyone -- most certainly not a club of former colonial powers.

What is the OECD problem?

Membership of the OECD means accepting the rules established by the pre-existing membership, and not being allowed to shape those rules. You must become a "rule-taker", rather than a "rule-maker" -- something which is not attractive to any emerging global power.

Perhaps the most onerous requirement of OECD membership is policy transparency, something which fragile democracies and authoritarian regimes are uncomfortable with. OECD committee meetings may be a little boring, but the deal is that all member countries open up with each other, and share detailed information on what's happening in their economy.

Most fundamentally, despite globalization, the OECD still remains a club of the West, substantially influenced by the US. And while joining a Western club may be attractive for countries like Costa Rica and Lithuania, it is not necessarily the case for the BRIICS.

The reality is that 25 years after the end of the Cold War, there is still a curtain between the West and the "Rest", even though it is no longer an iron curtain.

True, economic globalization is forging vast links between the West and "the Rest". Policy dialogue between governments is widespread. International tourism, students, and the Internet mean that there are also great webs of person-to-person contact.

But even in the best of cases, "the Rest" do not practice very well the Western values of pluralist democracy, respect for human rights and pluralist democracy. And resorting to conflict and harassment as means of international dispute resolution is now avoided wherever possible by Western countries, in contrast to countries like China and Russia. Perceived injustices from past history still motivate mindsets in these countries.

As to India, minor incidents, like the arrest of a junior diplomat for breaking the US law, can flair up into virtual nuclear warfare, highlighting the psychological scares of colonial history.

Assertive behavior by Australia in relation to boatloads of refugees passing through Indonesia to the vast Australian coastline has done immense damage to the always delicate Australia-Indonesia relationship. And the demise of Indonesia's Suharto regime at the hands of the Asian financial crisis, and arguably at the hands of the US-dominated International Monetary Fund, is still very much in living memory.

In short, despite the end of the Cold War, we are still a very long way from the end of history. Deep fundamental differences remain between the West and the "Rest".

And the West has contributed to this. America's credibility suffered greatly from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The global financial crisis represented a further shock for the West's brand of capitalism. The euro crisis has cast grave doubts over the benefits of close economic integration. Japan's never-ending crisis, which some interpret as being provoked by US pressure to revalue the yen, further undermine trust in American intentions -- could the US be trying to weaken China, as it succeeded in doing to Japan? And Snowdon's revelations of the National Security Agency's activities only deepened further the widespread distrust of the US.

All of this means that the OECD's one-time quest of becoming the "hub of globalization" will remain a pious hope. The Organisation is and will remain a vestige of Western dominance, despite its excellent work. In today's multi-polar world, the OECD just represents one pole!

In today's world, OECD membership is only attractive for small countries with great aspirations -- the Lilliputians of this world.

Author

John WestExecutive Director

Asian Century Institute