JAPAN

21 April 2014

Abenomics' false promise

Abenomics took Japan and the rest of the world by storm. But today Abenomics seems more like a mirage than a miracle cure.

Abenomics took Japan and the rest of the world by storm, with the promise that two lost decades of economic morosity and lack of political leadership had come to an end.

But today Abenomics seems more like a mirage than a miracle cure. Economic growth, investment and exports are faltering. The trade deficit is widening. The stock market has lost momentum, recording a sharp fall in the first quarter of 2014. Consumer confidence is fading. The only positive sign is the movement out of deflation into modest inflation.

Since the bursting of Japan's bubble economy over two decades ago, Asia's original miracle economy has stagnated, and experienced almost every possible economic ill.

Weak growth. Deflation. Government debt piling up. Income inequality. Informalization of the job market. Hollowing out of a once-proud manufacturing dynamo. Declining competitiveness vis-a-via Korea, Taiwan and China.

A loss of self confidence and sense of hopelessness has been an unavoidable consequence. This has inspired a resurgence of Japan's extreme right-wing. And this has certainly encouraged China to seize every pretext to bully Japan.

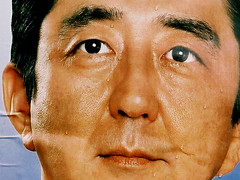

When Shinzo Abe returned to Japan's leadership a little over a year ago, it was by default, after the clumsy performance of the previous Democratic Party of Japan (left wing) administration.

But the advent of "Abenomics" provided an unexpected boost to a Japan that was looking for hope. Abenomics promised a revitalisation of the Japanese economy through expansionary monetary policy ("quantitative easing"), fiscal stimulus, and structural reform -- the "three arrows" of Abenomics.

Monetary expansion is designed to cure deflation (falling prices) which hold consumers back from spending money, and return inflation to 2% by 2015 -- an inflation rate which hasn't been seen since 1991. Its impact as been rapid -- prices are moving up, the stock market rallied driven by foreign capital, and the yen depreciated boosting exporters profits and competitiveness.

There is, however, no miracle cure in monetary expansion. Consumers and small businesses have lost out as import prices, especially for energy, have risen, and wages are falling in real terms (in fact, real wages have fallen by 5% over the past seven years). Big companies have been reluctant to give pay rises to workers, even though they are flush with accumulated profits.

In fact, consumer demand has been chronically weak for a long time in part because workers are now receiving less and less of the national economic pie, and have less and less money to spend. Labor's share of national income has dwindled from 66% to 60% over the past decade.

And since consumers are not spending, companies have no incentive to invest. In fact, many Japanese companies are much more interested in overseas markets, especially in Asia. As relations with China have become more problematic, they are shifting the focus of their investment to Indonesia, India, Burma and the Philippines, with great support from government agencies like JETRO, JBIC and the Japan Development Bank. Ironically, Abe's pro-business government seems to be doing more to help Japanese overseas, rather than, domestic investment.

Fiscal stimulus, Abenomics' second arrow, is just more of the same old thing from these past two decades. Spending money on infrastructure, of questionable value. All too often the real objective is to buy political support, or to fill the pockets of companies with close links to the government.

While this fiscal stimulus might create a few jobs, the resultant enormous public debt (now well over 200% if GDP) is undermining the economy. People are worried that they will have no pensions or health care when they retire, so they are again reluctant to spend.

The "big con" for fiscal stimulus will be paying off the local regions which are home to Japan's many nuclear power plants, to get their agreement to start the plants again. They have been turned off virtually ever since the March 11 triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown.

The business-dominated "nuclear village" is keen to start the nuclear power plants again, even though Japan, with its earthquake record is the last place on earth that should have nuclear power. Japan should now be focusing on renewable energy, especially its immense geothermal resources, rather than nuclear.

At the same time, the government is planning to progressively increase its consumption tax, as a measure to bring the public deficit and debt under control. It will rise from 5% to 8% on 1 April 2014, and further to 10% next year. But while comprehensive tax reform is required, citizens will bear the full brunt of an increasing consumption tax, which will depress demand further. Many commentators are expecting a post-tax slump to kick-in right now.

Structural reform, Abenomics third arrow, is an economics code word for removing all the unnecessary regulations, protections and favours that stop Japan from becoming once again a dynamic, innovative and entrepreneurial economy. Japan is simply riddled with this stuff. Moreover, as recent corporate governance scandals testify, as well as close links between Japanese business and the mafia (yakusa), Japanese business is run like an old boys club, with no culture of transparency, openness and accountability.

The structural reform agenda has always been a murky affair, being blocked by the vested interests of Japan's "iron triangle" of big business, stubborn bureaucrats and squabbling politicians.

Agricultural reform should be in the front line of the Trans Pacific Partnership trade talks. After all, Japanese agriculture is one of the advanced world's least efficient and is now withering away, with the average age of Japanese farmers being 66! But Japan is still stubbornly resisting reform.

Attempts to broker TPP agreement on agricultural reform ahead of President Obama's upcoming visit to Japan have failed. The presidential present will have to be, yet again, saki and sushi, not policy.

Japan should also open its economy to inward foreign investment. It has the most restrictive policies of any OECD country, and even North Korea had more foreign investment in relative terms than Japan. In the same way that Japanese investment has created lots of jobs and business overseas, Japan has much to gain from opening up to foreign investment.

One potentially exciting initiative is the creation of special economic zones, enveloping the main economic centers of Tokyo and Osaka, the details of which will be announced in the coming months. But it remains to be seen how much the regulatory burden will really be lightened.

Japan's present economic problems have progressively built up over the past two or three decades. The country is now sinking under the weight of a demographic drama (aging and declining population), exploding debt, the refusal of a conservative and inward-looking country to open to the rest of the world, and an old, male-dominated elite that inhibits the rebirth of an dynamic entrepreneurial economy.

While Abenomics has some good ideas, they will not provide a short term fix. Japan requires a deep and long process of reform. We may have to await a real crisis before that can start. Indeed, there is a high risk of an "Abegeddon" scenario where stagflation (inflation and weak growth) and a loss of confidence lead to capital flight and run on the government bond market.

Executive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com

But today Abenomics seems more like a mirage than a miracle cure. Economic growth, investment and exports are faltering. The trade deficit is widening. The stock market has lost momentum, recording a sharp fall in the first quarter of 2014. Consumer confidence is fading. The only positive sign is the movement out of deflation into modest inflation.

Since the bursting of Japan's bubble economy over two decades ago, Asia's original miracle economy has stagnated, and experienced almost every possible economic ill.

Weak growth. Deflation. Government debt piling up. Income inequality. Informalization of the job market. Hollowing out of a once-proud manufacturing dynamo. Declining competitiveness vis-a-via Korea, Taiwan and China.

A loss of self confidence and sense of hopelessness has been an unavoidable consequence. This has inspired a resurgence of Japan's extreme right-wing. And this has certainly encouraged China to seize every pretext to bully Japan.

When Shinzo Abe returned to Japan's leadership a little over a year ago, it was by default, after the clumsy performance of the previous Democratic Party of Japan (left wing) administration.

But the advent of "Abenomics" provided an unexpected boost to a Japan that was looking for hope. Abenomics promised a revitalisation of the Japanese economy through expansionary monetary policy ("quantitative easing"), fiscal stimulus, and structural reform -- the "three arrows" of Abenomics.

Monetary expansion is designed to cure deflation (falling prices) which hold consumers back from spending money, and return inflation to 2% by 2015 -- an inflation rate which hasn't been seen since 1991. Its impact as been rapid -- prices are moving up, the stock market rallied driven by foreign capital, and the yen depreciated boosting exporters profits and competitiveness.

There is, however, no miracle cure in monetary expansion. Consumers and small businesses have lost out as import prices, especially for energy, have risen, and wages are falling in real terms (in fact, real wages have fallen by 5% over the past seven years). Big companies have been reluctant to give pay rises to workers, even though they are flush with accumulated profits.

In fact, consumer demand has been chronically weak for a long time in part because workers are now receiving less and less of the national economic pie, and have less and less money to spend. Labor's share of national income has dwindled from 66% to 60% over the past decade.

And since consumers are not spending, companies have no incentive to invest. In fact, many Japanese companies are much more interested in overseas markets, especially in Asia. As relations with China have become more problematic, they are shifting the focus of their investment to Indonesia, India, Burma and the Philippines, with great support from government agencies like JETRO, JBIC and the Japan Development Bank. Ironically, Abe's pro-business government seems to be doing more to help Japanese overseas, rather than, domestic investment.

Fiscal stimulus, Abenomics' second arrow, is just more of the same old thing from these past two decades. Spending money on infrastructure, of questionable value. All too often the real objective is to buy political support, or to fill the pockets of companies with close links to the government.

While this fiscal stimulus might create a few jobs, the resultant enormous public debt (now well over 200% if GDP) is undermining the economy. People are worried that they will have no pensions or health care when they retire, so they are again reluctant to spend.

The "big con" for fiscal stimulus will be paying off the local regions which are home to Japan's many nuclear power plants, to get their agreement to start the plants again. They have been turned off virtually ever since the March 11 triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown.

The business-dominated "nuclear village" is keen to start the nuclear power plants again, even though Japan, with its earthquake record is the last place on earth that should have nuclear power. Japan should now be focusing on renewable energy, especially its immense geothermal resources, rather than nuclear.

At the same time, the government is planning to progressively increase its consumption tax, as a measure to bring the public deficit and debt under control. It will rise from 5% to 8% on 1 April 2014, and further to 10% next year. But while comprehensive tax reform is required, citizens will bear the full brunt of an increasing consumption tax, which will depress demand further. Many commentators are expecting a post-tax slump to kick-in right now.

Structural reform, Abenomics third arrow, is an economics code word for removing all the unnecessary regulations, protections and favours that stop Japan from becoming once again a dynamic, innovative and entrepreneurial economy. Japan is simply riddled with this stuff. Moreover, as recent corporate governance scandals testify, as well as close links between Japanese business and the mafia (yakusa), Japanese business is run like an old boys club, with no culture of transparency, openness and accountability.

The structural reform agenda has always been a murky affair, being blocked by the vested interests of Japan's "iron triangle" of big business, stubborn bureaucrats and squabbling politicians.

Agricultural reform should be in the front line of the Trans Pacific Partnership trade talks. After all, Japanese agriculture is one of the advanced world's least efficient and is now withering away, with the average age of Japanese farmers being 66! But Japan is still stubbornly resisting reform.

Attempts to broker TPP agreement on agricultural reform ahead of President Obama's upcoming visit to Japan have failed. The presidential present will have to be, yet again, saki and sushi, not policy.

Japan should also open its economy to inward foreign investment. It has the most restrictive policies of any OECD country, and even North Korea had more foreign investment in relative terms than Japan. In the same way that Japanese investment has created lots of jobs and business overseas, Japan has much to gain from opening up to foreign investment.

One potentially exciting initiative is the creation of special economic zones, enveloping the main economic centers of Tokyo and Osaka, the details of which will be announced in the coming months. But it remains to be seen how much the regulatory burden will really be lightened.

Japan's present economic problems have progressively built up over the past two or three decades. The country is now sinking under the weight of a demographic drama (aging and declining population), exploding debt, the refusal of a conservative and inward-looking country to open to the rest of the world, and an old, male-dominated elite that inhibits the rebirth of an dynamic entrepreneurial economy.

While Abenomics has some good ideas, they will not provide a short term fix. Japan requires a deep and long process of reform. We may have to await a real crisis before that can start. Indeed, there is a high risk of an "Abegeddon" scenario where stagflation (inflation and weak growth) and a loss of confidence lead to capital flight and run on the government bond market.

Author

John WestExecutive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com