JAPAN

25 March 2014

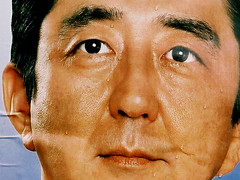

Abenomics must bring seismic change to Japan

The cherry blossoms appeared ten days early this year. And optimism has returned to Japan with its new government led by Shinzo Abe. But "Abenomics" must bring seismic change to Japan.

The cherry blossoms appeared ten days early in Tokyo this year. And optimism has returned to Japan with its new government led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Abe's new strategy involves a cocktail of "three arrows" -- fighting deflation, infrastructure spending and structural reform. ("Three arrows cannot be broken" is a Japanese proverb.)

But "Abenomics" must bring seismic change to Japan. Technical economic policy adjustments will not do. Japan needs to complete its social modernization and economic democratization to fulfill the country's dreams.

To be sure, aggressive monetary action to tackle deflation is a worthwhile experiment (even though deflation has also become a psychological phenomenon in Japan). Deflation and an overvalued exchange rate have been pulling the Japanese economy down for a long time. And well-spent, infrastructure spending can provide a useful filip to growth, even though it will also add to public debt.

Abe's commitment to join the US-led Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) is welcome, even though he will come under enormous domestic pressure to delay difficult reforms. But details and commitments on other structural reforms have not been outlined. And although Abe has enlisted the reformist zeal of Internet businessman Hiroshi Mikitani to his industrial competitiveness panel, Japan's tradition of "kabuki-talk" on structural reforms will be hard to break.

In fact, Japan has many deep-rooted issues to be tackled for it and its citizens to realize their immense potential, and to stop the country fading away as an economic power.

The substantial exclusion of women from full participation in Japan's economy, society and politics is well-known. The World Economic Forum ranks Japan 101 out of the 135 countries in its Global Gender Gap Index, well below China. And the IMF has estimated that if the participation of Japanese women in the labor force rose to the level of northern Europe, the country's GDP per capita would be permanently 9% higher. Also, if female participation rates converged Japanese male levels over the next 20 years, Japan could avoid most of the projected further decline of its labor force.

Family-friendly social and work policies could make a major contribution to improving the female participation rate. Such policies could also help increase Japan's extremely low birth rate. But more fundamentally, Japan needs to put an end to deep-seated work-place discrimination against women.

Greater participation of older workers could also contribute to a stronger Japan. The country has the highest life expectancy among the advanced OECD countries (83 years), and yet the Japanese typically retire at age 60. More flexible employment and wage systems could enable them to work longer. And if the pension eligibility age were lifted in tandem, this would generate useful fiscal savings in this overly indebted country.

As Japan has seen growing labour market "dualism" in recent years, perhaps up to one half of young workers now find themselves in "non-regular" forms of employment, like temporary, part-time and temporary work agency jobs. You can see hordes of them working at Starbucks and other cafe chains. These jobs provide low income and social insurance coverage, and fewer skill development opportunities. And once you are in the non-regular track in Japan, there are very few ways back out of precarious employment. This is resulting in a great waste of the potential of the nation's youth.

High protection for agriculture has cost the country financially, irritated trading partners, limited Japan's capacity to enter into free trade agreements, prevented it from becoming a global leader in high-quality and high-value agricultural products (like Japan's Fuji apples), and failed to save jobs at the same time. And vast regulations and other market barriers mean that Japan has very low productivity in its service sector. Japan is a laggard in a wide range of global services like finance, education, health, and business consulting. There is also great scope to improve efficiency in domestic service industries like retail, energy and transport.

Despite massive investments in R&D, Japan's innovation performance has been weak. Thus, Japan's once leading electronic giants like Sony, Panasonic and Sharp are now losing billions, and are being beaten on international markets by firms from the US (such as Apple), Korea (like Samsung) and China. They were overtaken by the digital revolution.

Japan has a vast agenda for becoming an innovation-driven, service-based economy, including: stronger competition and regulatory reforms; better cooperation among universities, government and research institutes; upgrading tertiary education; greater exposure to international markets; and participation in international research networks.

Among the OECD countries, Japan has the lowest level of imports and inflows of FDI as a share of GDP, and the lowest share of foreigners in the labor force. Greater openness to imports and FDI would boost competition, efficiency and innovation. And most importantly FDI would enable domestic Japan to join regional and international supply chains especially in the services sector. Moving ahead with the TPP and Economic Partnership Agreements with its neighbors is critical to the health of the Japanese economy and to shifting to a two-way globalization.

When Japanese enterprises get into financial trouble, "Japan Inc" typically comes to their rescue with banking finance. Big companies rarely go bankrupt in Japan. Just think of Japan Airlines which has received several bailouts compared with PanAm which went bankrupt in 1991.

Japan's vast conglomerates also do their best to avoid closing down loss-making divisions. And today many nonviable small and medium sized companies are kept afloat by low interest rates and public credit support measures.

This is very costly. Government support should be phased out. Restructuring is necessary, even if it pushes up unemployment in the short term. Banks would have to recognize non-performing loans. Some may need to be consolidated and have their capital base strengthened.

In a market economy, we should never resist change, and hang to the past. Moreover, we must always create space for the new. In this regard, Japan needs to promote entrepreneurship and a more business-friendly environment, particularly by reducing the administrative burden on business start-ups. And credit should be made available to new dynamic innovative enterprises, and the supply of risk money, such as venture capital, for R&D and innovative business start-ups should be promoted.

But Japan is in desperate need of migrants to do "3D" jobs (dirty, difficult and dangerous). It also needs more migrants as care-givers for its rapidly ageing population. Reflecting their needs, there has been some increase in immigration. But this has all too often taken irregular forms like "trainees", "entertainers", marriage migration, toleration of illegal migrants and even human trafficking. This means that too many migrants have precarious situations and are vulnerable to abuse. And moreover, this reduces their potential contribution to the Japanese economy and society.

For its own future benefit, Japan needs to see migrants as beneficial to its economy and assets to its community, rather than a liability. It also needs to look to the example of countries like the US where diversity has been a great strength. It has been estimated that immigrant-founded technology companies in the US generated $52 billion in revenues and created 450,000 jobs between 1995 and 2005.

And embracing diversity also has a domestic dimension. Unconventional, dynamic entrepreneurs like Hiroshi Mikitani (Rakuten) and Masayoshi Son (Softbank) are sadly treated as mavericks by the Japanese business establishment. This is in contrast to the US where successful entrepreneurs like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg are treated as national heros.

For example, Japan is not a leading destination for international students, in part because English is the language of international education. Despite the immense beauty of the country, Japan receives a very low number of foreign tourists. Japan's R&D capacities are also hindered as many researchers cannot participate in international networks.

This has been recognized by Hiroshi Mikitani, CEO of Rakuten, Japan's answer to Amazon. "Mickey", as he is known to his employees, requires them all to speak English at work ("Englishnization"). But this is a unique case. It was not surprisingly dismissed as "stupid" by Honda president Takanobu Ito in 2010

The benefits are however quite obvious. All employees in this global company can now speak with each other without an interpreter. And since staff even in Tokyo don't need to speak Japanese, Mikitani can attract a broader pool of global talent. Staff are also better able to keep tabs on and benchmark global competitors.

But there are also other costs to Japan's poor English language capability. Japan is widely considered to be an outsider in the international community, and has not been very effective in presenting its case in international disputes such as the case with China over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

But Japan is a country that has lost its "mojo". It stands on a precipice in its modern history with: a rapidly aging and declining population; chronically sluggish economy; weak productivity and innovation performance; massive public debt; difficult relations with some of its neighbors; and until recently, a lack of political leadership.

Abenomics is a brave attempt to restart the Japanese machine. But "Abenomics" must bring seismic change to Japan.

Prime Minister Abe's recruitment of radical businessman Hiroshi Mikitani is a positive sign, as his Japan Association of New Economy is creating a roadmap to the economic revival of Japan, with Abe's encouragement. This will be important because much more than technical economic policy adjustments are necessary. Japan needs to complete its social modernization and economic democratization to fulfill country's dreams.

Executive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com

Abe's new strategy involves a cocktail of "three arrows" -- fighting deflation, infrastructure spending and structural reform. ("Three arrows cannot be broken" is a Japanese proverb.)

But "Abenomics" must bring seismic change to Japan. Technical economic policy adjustments will not do. Japan needs to complete its social modernization and economic democratization to fulfill the country's dreams.

To be sure, aggressive monetary action to tackle deflation is a worthwhile experiment (even though deflation has also become a psychological phenomenon in Japan). Deflation and an overvalued exchange rate have been pulling the Japanese economy down for a long time. And well-spent, infrastructure spending can provide a useful filip to growth, even though it will also add to public debt.

Abe's commitment to join the US-led Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) is welcome, even though he will come under enormous domestic pressure to delay difficult reforms. But details and commitments on other structural reforms have not been outlined. And although Abe has enlisted the reformist zeal of Internet businessman Hiroshi Mikitani to his industrial competitiveness panel, Japan's tradition of "kabuki-talk" on structural reforms will be hard to break.

In fact, Japan has many deep-rooted issues to be tackled for it and its citizens to realize their immense potential, and to stop the country fading away as an economic power.

Japan must offer all its citizens the opportunity to fully participate in the economy.

In a country where the working age population has been declining for many years, and where the population is now falling, it is imperative for Japan to offer all its citizens the opportunity to fully participate in the economy.The substantial exclusion of women from full participation in Japan's economy, society and politics is well-known. The World Economic Forum ranks Japan 101 out of the 135 countries in its Global Gender Gap Index, well below China. And the IMF has estimated that if the participation of Japanese women in the labor force rose to the level of northern Europe, the country's GDP per capita would be permanently 9% higher. Also, if female participation rates converged Japanese male levels over the next 20 years, Japan could avoid most of the projected further decline of its labor force.

Family-friendly social and work policies could make a major contribution to improving the female participation rate. Such policies could also help increase Japan's extremely low birth rate. But more fundamentally, Japan needs to put an end to deep-seated work-place discrimination against women.

Greater participation of older workers could also contribute to a stronger Japan. The country has the highest life expectancy among the advanced OECD countries (83 years), and yet the Japanese typically retire at age 60. More flexible employment and wage systems could enable them to work longer. And if the pension eligibility age were lifted in tandem, this would generate useful fiscal savings in this overly indebted country.

As Japan has seen growing labour market "dualism" in recent years, perhaps up to one half of young workers now find themselves in "non-regular" forms of employment, like temporary, part-time and temporary work agency jobs. You can see hordes of them working at Starbucks and other cafe chains. These jobs provide low income and social insurance coverage, and fewer skill development opportunities. And once you are in the non-regular track in Japan, there are very few ways back out of precarious employment. This is resulting in a great waste of the potential of the nation's youth.

Japan must complete its economic development to become an innovation-driven, service-based economy.

The rise of the Japan in the post-war period was driven by a high-class manufacturing sector especially in the automobile and electronics sectors. Japan absorbed technology and knowledge from overseas, and then often adapted and perfected it through "incremental innovation". This could be seen in the Japanese manufacturing concepts of "continuous improvement" and "just-in-time". But Japan has failed to modernize its agriculture and service sectors.High protection for agriculture has cost the country financially, irritated trading partners, limited Japan's capacity to enter into free trade agreements, prevented it from becoming a global leader in high-quality and high-value agricultural products (like Japan's Fuji apples), and failed to save jobs at the same time. And vast regulations and other market barriers mean that Japan has very low productivity in its service sector. Japan is a laggard in a wide range of global services like finance, education, health, and business consulting. There is also great scope to improve efficiency in domestic service industries like retail, energy and transport.

Despite massive investments in R&D, Japan's innovation performance has been weak. Thus, Japan's once leading electronic giants like Sony, Panasonic and Sharp are now losing billions, and are being beaten on international markets by firms from the US (such as Apple), Korea (like Samsung) and China. They were overtaken by the digital revolution.

Japan has a vast agenda for becoming an innovation-driven, service-based economy, including: stronger competition and regulatory reforms; better cooperation among universities, government and research institutes; upgrading tertiary education; greater exposure to international markets; and participation in international research networks.

Japan must shift from one-way to two-way globalization

Japan's initial take-off 60 years ago was propelled by highly competitive exports. Then as domestic costs rose and it faced protectionism in Western markets, Japanese companies made large overseas investments to shift their production offshore. But Japan's globalization has always been "one-way". Closed and highly regulated domestic markets held back imports and perhaps more importantly foreign direct investment (FDI).Among the OECD countries, Japan has the lowest level of imports and inflows of FDI as a share of GDP, and the lowest share of foreigners in the labor force. Greater openness to imports and FDI would boost competition, efficiency and innovation. And most importantly FDI would enable domestic Japan to join regional and international supply chains especially in the services sector. Moving ahead with the TPP and Economic Partnership Agreements with its neighbors is critical to the health of the Japanese economy and to shifting to a two-way globalization.

Japan must accept creative destruction as the key to a prosperous market economy

Japan's large enterprises and trading houses typically have long and proud histories. Sumitomo traces its origins back to the creation of the Sumitomo store in 1640! But Japan has very few corporate champions which were established in recent decades. This is in sharp contrast to the US, the land of "creative destruction", where an important number of corporate champions like Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook have been created in recent decades.When Japanese enterprises get into financial trouble, "Japan Inc" typically comes to their rescue with banking finance. Big companies rarely go bankrupt in Japan. Just think of Japan Airlines which has received several bailouts compared with PanAm which went bankrupt in 1991.

Japan's vast conglomerates also do their best to avoid closing down loss-making divisions. And today many nonviable small and medium sized companies are kept afloat by low interest rates and public credit support measures.

This is very costly. Government support should be phased out. Restructuring is necessary, even if it pushes up unemployment in the short term. Banks would have to recognize non-performing loans. Some may need to be consolidated and have their capital base strengthened.

In a market economy, we should never resist change, and hang to the past. Moreover, we must always create space for the new. In this regard, Japan needs to promote entrepreneurship and a more business-friendly environment, particularly by reducing the administrative burden on business start-ups. And credit should be made available to new dynamic innovative enterprises, and the supply of risk money, such as venture capital, for R&D and innovative business start-ups should be promoted.

Japan must embrace diversity

The Japanese people are very proud of their perceived uniqueness and cultural homogeneity. And it is largely for this reason that Japan has very restrictive immigration policies.But Japan is in desperate need of migrants to do "3D" jobs (dirty, difficult and dangerous). It also needs more migrants as care-givers for its rapidly ageing population. Reflecting their needs, there has been some increase in immigration. But this has all too often taken irregular forms like "trainees", "entertainers", marriage migration, toleration of illegal migrants and even human trafficking. This means that too many migrants have precarious situations and are vulnerable to abuse. And moreover, this reduces their potential contribution to the Japanese economy and society.

For its own future benefit, Japan needs to see migrants as beneficial to its economy and assets to its community, rather than a liability. It also needs to look to the example of countries like the US where diversity has been a great strength. It has been estimated that immigrant-founded technology companies in the US generated $52 billion in revenues and created 450,000 jobs between 1995 and 2005.

And embracing diversity also has a domestic dimension. Unconventional, dynamic entrepreneurs like Hiroshi Mikitani (Rakuten) and Masayoshi Son (Softbank) are sadly treated as mavericks by the Japanese business establishment. This is in contrast to the US where successful entrepreneurs like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg are treated as national heros.

Japan must join the global community by learning the English language.

The level of English language capability in Japan is very poor, even behind North Korea, according to some estimates. This is very costly for Japan. English is the language of international business, and Japan's poor English capacities hold it back in international services trade.For example, Japan is not a leading destination for international students, in part because English is the language of international education. Despite the immense beauty of the country, Japan receives a very low number of foreign tourists. Japan's R&D capacities are also hindered as many researchers cannot participate in international networks.

This has been recognized by Hiroshi Mikitani, CEO of Rakuten, Japan's answer to Amazon. "Mickey", as he is known to his employees, requires them all to speak English at work ("Englishnization"). But this is a unique case. It was not surprisingly dismissed as "stupid" by Honda president Takanobu Ito in 2010

The benefits are however quite obvious. All employees in this global company can now speak with each other without an interpreter. And since staff even in Tokyo don't need to speak Japanese, Mikitani can attract a broader pool of global talent. Staff are also better able to keep tabs on and benchmark global competitors.

But there are also other costs to Japan's poor English language capability. Japan is widely considered to be an outsider in the international community, and has not been very effective in presenting its case in international disputes such as the case with China over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

Conclusion

Japan achieved a phenomenal renaissance after World War 2, thanks to outstanding manufacturing companies that conquered world markets, supported by a highly-educated and hard-working population, and a government that made very good investments in hard infrastructure.But Japan is a country that has lost its "mojo". It stands on a precipice in its modern history with: a rapidly aging and declining population; chronically sluggish economy; weak productivity and innovation performance; massive public debt; difficult relations with some of its neighbors; and until recently, a lack of political leadership.

Abenomics is a brave attempt to restart the Japanese machine. But "Abenomics" must bring seismic change to Japan.

Prime Minister Abe's recruitment of radical businessman Hiroshi Mikitani is a positive sign, as his Japan Association of New Economy is creating a roadmap to the economic revival of Japan, with Abe's encouragement. This will be important because much more than technical economic policy adjustments are necessary. Japan needs to complete its social modernization and economic democratization to fulfill country's dreams.

Author

John WestExecutive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com

REFERENCES:

- Why Abenomics will work by Joseph Stiglitz. Sydney Morning Herald, April 11, 2013- World Economic Forum. The Global Gender Gap Report 2012.

- OECD. Economic Survey of Japan 2011.

- Can Women Save Japan? Chad Steinberg and Masato Nakane. IMF Working Paper, WP/12/248.

- What Role Can Financial Policies Play in Revitalizing SMEs in Japan? Raphael Lam and Jongsoon Shin. IMF Working Paper No. 12/291