CHINA

23 June 2014

China's elites and development

Over three decades ago, China's Communist Party elite saw it in its interest to adopt pro-development policies. But now elites are challenged by the consequences of their own strategy.

Over three decades ago, China's Communist Party elite saw it in its interest to adopt pro-development policies. This is in sharp contrast to most countries in the Middle East and North Africa whose elites squandered development opportunities and plundered their countries. The frustrations that this caused, ultimately gave rise to the regional uprising known as the "Arab Spring".

China's strong economic performance has strengthened the Communist Party's legitimacy in the eyes of large numbers of Chinese citizens, especially those who benefited most from economic development. Perhaps ironically, however, China's elite now finds itself threatened by the consequences of its own success.

Dramatic economic growth has been accompanied by large scale corruption, widening income gaps between rich and poor, immense environmental damage, many scandals and growing social unrest. More fundamentally, China now has a much more complex and diverse society, which is more prosperous, better educated and informed, and demands greater freedom. As we have witnessed through the recent Communist Party Congress, the reaction of Chinese authorities has been to stiffen political and social repression.

Let's first delve into the question of elites and economic development.

The United Nations University has defined elites as "a distinct group within a society which enjoys privileged status and exercises decisive control over the organization of society". Countries typically have political, business and educated elite groups which are distinct groups, but are also interconnected.

The power of elites exceeds their actual representation within society because of their control over a nation's productive assets and institutions.

Elites can choose to use their assets and resources in productive, innovative and entrepreneurial ways that promote economic development, employment and reduce income inequality. Alternatively, elites can act as rent-seekers, can direct resources towards their own social groups, or overexploit natural resources without regard for longer term sustainability.

Elites also control political decision-making processes in society, and can design and implement institutions that favour their interests. They can also influence how both elites and non-elites perceive different issues through their control and presentation of information, and their influence over the media, even when it is "free".

In short, if elites can be induced to adopt pro-development policies, rather than predatory behaviour, they can have a very positive impact on development. For example, Lee Kwan Yew in Singapore, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, and Bill Gates in the United States changed the direction of development from their elite positions.

So how did China's elite (some 200 or so families) become motivated by a pro-development agenda?

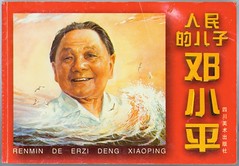

Deng Xiaoping took over the leadership of China in 1978, following several decades of centrally planned economics under Mao Zedong. While some progress had been made under Mao, especially for health and education, China's overall economic situation was very poor, especially compared with its Asian neighbours like Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong. Of particular interest to China was that most of these economies achieved success by mixing market-based economics with non-democratic politics.

In a way, Deng's motivation was the same as Mao's, that is, a strong economy, regime stability and opportunities for corruption. This is how China has functioned for over 2000 years. But Deng could see that market economics (rather than central planning) was the best way to achieve this.

China's development path launched by Deng has been abundantly successful. Rapid economic growth has reduced poverty dramatically, a big positive in terms of its legitimacy with the Chinese public. The gap between rich and poor has widened dramatically, meaning that the elite has won more from development than the masses. And rampant corruption has also helped the elite benefit.

The ever pragmatic Deng once said, as he defended market economics against central planning, that it does not matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice. But once the market economics "cat is out of the bag" it creates a whole new world of challenges.

Chinese citizens are economically much better off than they were before reform started, and they have much greater freedom. But many citizens are discontent with corruption, widening income gaps between rich and poor, environmental damage and official abuses like land grabs. And as is clear from China's cyber-world and its 500 million Internet users, many Chinese citizens, especially the young, want freedom and honesty.

The Party has promoted nationalism (especially anti-Japanese attitudes) as a force for social cohesion and political stability. This has proved to be a volatile and difficult-to-control tonic, and is very costly.

China's belicose behavior in the East China and South China Seas means that it has very few friends in its region, and it is now a much less attractive investment destination. And the Chinese public's passion for American movies, music, basketball and fastfood undermine the Party's efforts to strengthen the soft power of Chinese culture.

As the recent Communist Party Congress has highlighted, societal diversity and complexity is also matched by the diverse and complex interests of the main factions of the Communist Party. Over time, this could threaten the Communist Party's hold on power. There is even speculation that the Party might tear itself apart!

The new Chinese leadership "elected" at the recent Communist Party Congress, seems a cautious, conservative bunch. Consensual decision-making, and the desire for stability, means that rapid ecnomic reform is unlikely, and political reform is off the agenda. But for its own long-term survival, the Communist Party needs to overcome political paralysis and gridlock, and launch a new wave of economic reforms.

China has entered the zone where developing countries usually become democratic, as Korea and Taiwan did. While there is much debate about whether the Chinese people want democracy, there is no doubt that they want better governance.

There are many things that the Chinese government could do to improve governance, even without moving to electoral democracy. First, they should improve the rule of law by giving independence to the judicial system and the police force, which are presently corrupt and under the influence of Communist Party officials.

Second, they should give much greater freedom to the media and civil society organizations. Third, government should become transparent and accountable, especially regarding its finances. Fourth, some privatization and more honest governance of state-owned enterprises is critical -- at present, lots of profits and assets are siphoned off into overseas bank accounts.

The best way for the Communist Party elite to hang on to its one-party system is to improve the quality of its governance through measures such as these. This is one of the lessons from Singapore, a case that China has studied closely for lessons.

Are the Chinese government and the Communist Party elite capable of undertaking such reforms? It seems doubtful.

The elites which three decades ago, saw it in their interests to reform for their very own survival, today seem entangled in a vast complex system of crony capitalism that ties together state-owned business and government. And the passage of three decades means that there is now a whole new generation of children, other relatives and friends who are part of this bamboo network of crony capitalism.

The government's knee-jerk reaction is to ramp up the social and political repression. But experience shows that you can't keep the lid on a pressure cooker forever!

This situation is a great pity. There would be many unpredictable consequences from a major economic and political crisis in China. And this would be in no-one's interests.

"May you live in interesting times" is an oft-quoted Chinese saying. In reality, it is a curse!

Executive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com

China's strong economic performance has strengthened the Communist Party's legitimacy in the eyes of large numbers of Chinese citizens, especially those who benefited most from economic development. Perhaps ironically, however, China's elite now finds itself threatened by the consequences of its own success.

Dramatic economic growth has been accompanied by large scale corruption, widening income gaps between rich and poor, immense environmental damage, many scandals and growing social unrest. More fundamentally, China now has a much more complex and diverse society, which is more prosperous, better educated and informed, and demands greater freedom. As we have witnessed through the recent Communist Party Congress, the reaction of Chinese authorities has been to stiffen political and social repression.

Let's first delve into the question of elites and economic development.

The United Nations University has defined elites as "a distinct group within a society which enjoys privileged status and exercises decisive control over the organization of society". Countries typically have political, business and educated elite groups which are distinct groups, but are also interconnected.

The power of elites exceeds their actual representation within society because of their control over a nation's productive assets and institutions.

Elites can choose to use their assets and resources in productive, innovative and entrepreneurial ways that promote economic development, employment and reduce income inequality. Alternatively, elites can act as rent-seekers, can direct resources towards their own social groups, or overexploit natural resources without regard for longer term sustainability.

Elites also control political decision-making processes in society, and can design and implement institutions that favour their interests. They can also influence how both elites and non-elites perceive different issues through their control and presentation of information, and their influence over the media, even when it is "free".

In short, if elites can be induced to adopt pro-development policies, rather than predatory behaviour, they can have a very positive impact on development. For example, Lee Kwan Yew in Singapore, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, and Bill Gates in the United States changed the direction of development from their elite positions.

So how did China's elite (some 200 or so families) become motivated by a pro-development agenda?

Deng Xiaoping took over the leadership of China in 1978, following several decades of centrally planned economics under Mao Zedong. While some progress had been made under Mao, especially for health and education, China's overall economic situation was very poor, especially compared with its Asian neighbours like Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong. Of particular interest to China was that most of these economies achieved success by mixing market-based economics with non-democratic politics.

In a way, Deng's motivation was the same as Mao's, that is, a strong economy, regime stability and opportunities for corruption. This is how China has functioned for over 2000 years. But Deng could see that market economics (rather than central planning) was the best way to achieve this.

China's development path launched by Deng has been abundantly successful. Rapid economic growth has reduced poverty dramatically, a big positive in terms of its legitimacy with the Chinese public. The gap between rich and poor has widened dramatically, meaning that the elite has won more from development than the masses. And rampant corruption has also helped the elite benefit.

The ever pragmatic Deng once said, as he defended market economics against central planning, that it does not matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice. But once the market economics "cat is out of the bag" it creates a whole new world of challenges.

Chinese citizens are economically much better off than they were before reform started, and they have much greater freedom. But many citizens are discontent with corruption, widening income gaps between rich and poor, environmental damage and official abuses like land grabs. And as is clear from China's cyber-world and its 500 million Internet users, many Chinese citizens, especially the young, want freedom and honesty.

The Party has promoted nationalism (especially anti-Japanese attitudes) as a force for social cohesion and political stability. This has proved to be a volatile and difficult-to-control tonic, and is very costly.

China's belicose behavior in the East China and South China Seas means that it has very few friends in its region, and it is now a much less attractive investment destination. And the Chinese public's passion for American movies, music, basketball and fastfood undermine the Party's efforts to strengthen the soft power of Chinese culture.

As the recent Communist Party Congress has highlighted, societal diversity and complexity is also matched by the diverse and complex interests of the main factions of the Communist Party. Over time, this could threaten the Communist Party's hold on power. There is even speculation that the Party might tear itself apart!

The new Chinese leadership "elected" at the recent Communist Party Congress, seems a cautious, conservative bunch. Consensual decision-making, and the desire for stability, means that rapid ecnomic reform is unlikely, and political reform is off the agenda. But for its own long-term survival, the Communist Party needs to overcome political paralysis and gridlock, and launch a new wave of economic reforms.

China has entered the zone where developing countries usually become democratic, as Korea and Taiwan did. While there is much debate about whether the Chinese people want democracy, there is no doubt that they want better governance.

There are many things that the Chinese government could do to improve governance, even without moving to electoral democracy. First, they should improve the rule of law by giving independence to the judicial system and the police force, which are presently corrupt and under the influence of Communist Party officials.

Second, they should give much greater freedom to the media and civil society organizations. Third, government should become transparent and accountable, especially regarding its finances. Fourth, some privatization and more honest governance of state-owned enterprises is critical -- at present, lots of profits and assets are siphoned off into overseas bank accounts.

The best way for the Communist Party elite to hang on to its one-party system is to improve the quality of its governance through measures such as these. This is one of the lessons from Singapore, a case that China has studied closely for lessons.

Are the Chinese government and the Communist Party elite capable of undertaking such reforms? It seems doubtful.

The elites which three decades ago, saw it in their interests to reform for their very own survival, today seem entangled in a vast complex system of crony capitalism that ties together state-owned business and government. And the passage of three decades means that there is now a whole new generation of children, other relatives and friends who are part of this bamboo network of crony capitalism.

The government's knee-jerk reaction is to ramp up the social and political repression. But experience shows that you can't keep the lid on a pressure cooker forever!

This situation is a great pity. There would be many unpredictable consequences from a major economic and political crisis in China. And this would be in no-one's interests.

"May you live in interesting times" is an oft-quoted Chinese saying. In reality, it is a curse!

Author

John WestExecutive Director

Asian Century Institute

www.asiancenturyinstitute.com

REFERENCES:

- United Nations University. World Institute for Development Economics Research. Aligning Elites with Development, Alice Amsden, Alisa DiCaprio, and James Robinson.- Xiaowei Zang. Why are the Elite in China Motivated to Promote Growth. United Nations University. World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- This article has also been published by the Global Economic Intersection